Some things in this world just don’t make sense—no matter how you slice it. Take the zebrafish, for example. A tiny, transparent freeloader that wouldn’t even pick it as bait, much less any fishing dude’s Instagram story. And yet—somehow—it ended up becoming a pillar of modern life sciences. Yeah, I know. It sounds ridiculous. So, how did this happen? Let’s rewind.

1. A Tiny Life, Barely Noticed

Do you know where zebrafish originally come from?

The Indo-Gangetic plains. Yep, that Ganges.

They swim through rice paddies, floodplains, and puddles across India, Nepal, and Bangladesh. But here’s the kicker—even the most devout Brahmins probably never realized that among all those sacred waters swam a future scientific superstar. Because let’s be honest, there are probably hundreds of tiny fish in the Ganges with similar vibes—same look, same lifestyle, same “eat or be eaten” game—nothing to set the zebrafish apart… at first glance.

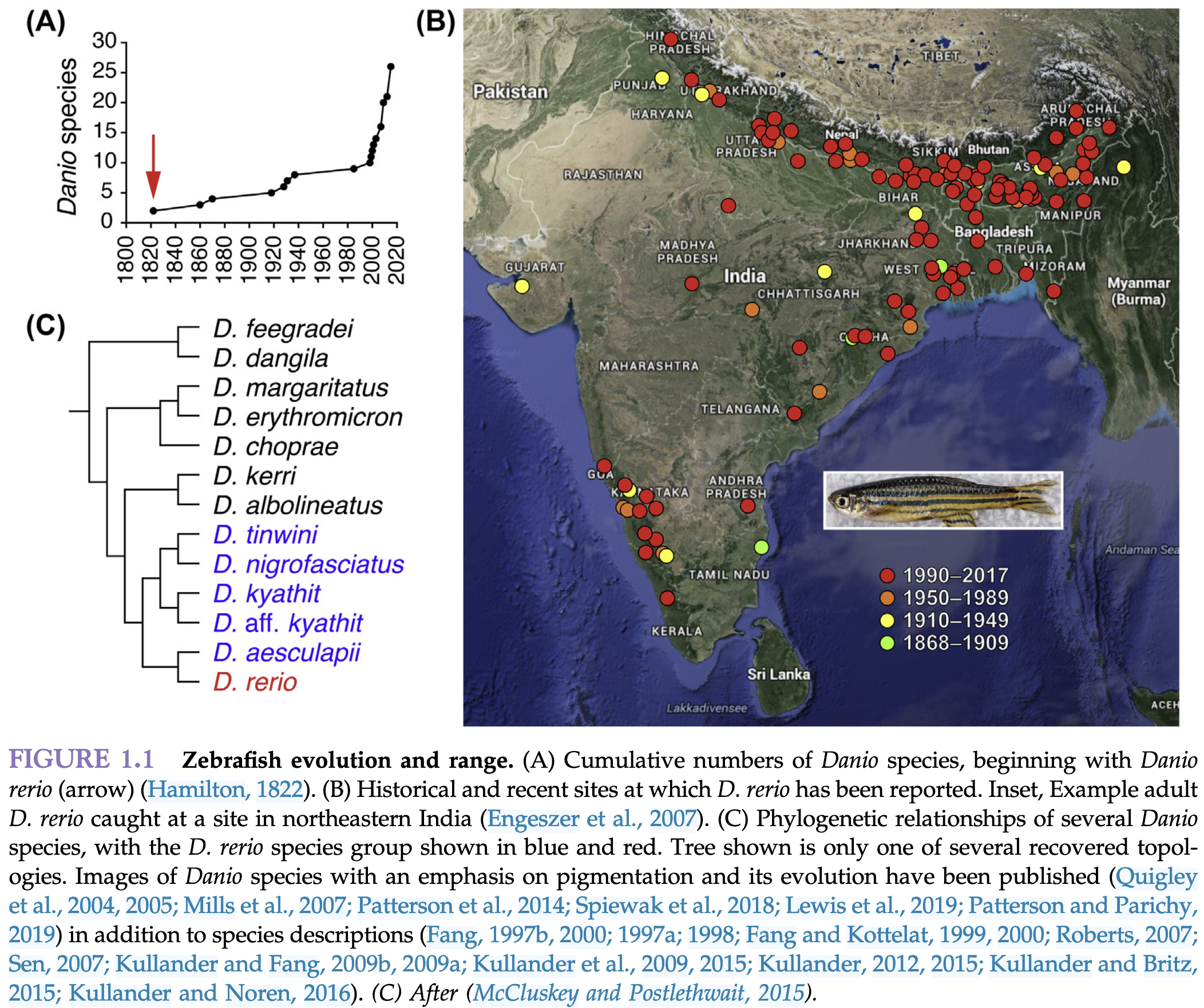

From Parichy DM 2020.

From Parichy DM 2020.

In fact, one theory suggests that the zebrafish’s signature stripes might act like a barcode to distinguish each other from other kinds of fish, especially during mating season, when things can get… confusing. Their stripes like fish Tinder, but with better lighting. Knock out a single gene, and suddenly these fish are socially awkward loners Patterson LB 2019. But honestly? Even if they mix things up, who cares? Zebrafish aren’t exactly known for their family members. They can snack on their own eggs even when they’re not hungry. Monogamy? Parenting instincts? Never heard of ‘em. You gotta feel bad for zebrafish—seriously. From the very first day they’re born, everything that moves (including mom and dad) is basically like: “Yup, dinner’s served.” Their only chance at survival? Turn the opacity slider all the way down and hope everyone nearby suddenly develops selective blindness. But let’s face it, invisibility only gets you so far in this brutal ecosystem. So, they’ve also mastered the ancient art of strategic hiding—wiggling into shallow puddles where the big fish don’t bother going. Oh, and as carp family members, they’ve unlocked full-on apocalypse mode: dirty water? No problem. Low oxygen? Bring it on. These fish weren’t made to thrive—they were built to survive.

2. When the World First Noticed

Back in 1822, a Scottish physician stumbled across a small, inconspicuous fish swimming in the rice paddies of northern India. That fish? The now-famous zebrafish. But back then? Just another tiny nobody in a sea of forgettable minnows. Discovered—and promptly forgotten. After all, the world was (and still is) full of small, unremarkable fish. What made this one any different? And then, as if by fate, something game-changing appeared on the scene. Any guesses?

It wasn’t a microscope. Not a supercomputer. It was… a glass box. Yup—a square, transparent fish tank.

When this new invention—the square glass aquarium—was unveiled at the 1851 Great Exhibition in London, it didn’t just make a splash. It sparked an ornamental fish revolution. Before that, people kept fish in ceramic basins or weirdly shaped glass jars where small creatures were either blocked from view or visually distorted. So, naturally, hobbyists gravitated toward the big, flashy ones—goldfish, koi, and the like. But now? With the crystal-clear side view of a modern glass tank, even the tiniest fish could finally shine. Visibility meant viability in marketing. Suddenly, little fish all over the world had a shot at stardom.

And just like that, the zebrafish got its lucky break. India—being the freshwater fish paradise that it is—quickly became a hotspot for this ornamental fish gold rush. And the zebrafish? Cheap, easy to care for, low maintenance—basically the ideal roommate. Before long, it was showing up in aquariums across the globe. By the early 20th century, the zebrafish had become a regular in the Western ornamental fish scene—an NPC in every pet store’s background tank. But here’s where things got interesting.

You see, the phrase “Century of Life Sciences” wasn’t coined today (21st century)—it was originally meant to describe the 20th century itself. Microscopes were getting sharper. Staining techniques were improving. Fields like cytology, embryology, genetics, and physiology were booming. Papers were pouring out like viral TikToks. And biomedical grad students? Let’s just say getting a PhD back then was way easier than it is today. As science marched into the 20th century, researchers began circling back to one of life’s biggest unsolved mysteries: How does a single fertilized egg—a lone cell—somehow transform into a living, breathing organism, complete with muscles, nerves, eyeballs, and the occasional existential crisis?

Of course, cracking that code isn’t easy. Why? Because embryos love to stay hidden—either deep inside a body, or wrapped in layers of opaque egg jelly. You just… can’t see what’s going on. Enter 1934. At Wayne State University, a researcher named Charles W. Creaser was—well, possibly procrastinating on something—when he stumbled upon a curious little fish. He took a closer look and had a bit of a eureka moment: “Hey, this fish? It’s transparent. The embryos? Develop externally. The eggs? Not picky about water. Stick it under a microscope and boom—you’ve got yourself a live broadcast of embryonic development.” Nature’s own reality show. No subscription required.

Reality show of development of Zebrafish embryo. Figures are from Kimmel CB 1995. Videos are from @TushnaKapoor in EMBOcellPolarity25 (https://x.com/HeisenbergCPLab/status/1930179868437721213).

Reality show of development of Zebrafish embryo. Figures are from Kimmel CB 1995. Videos are from @TushnaKapoor in EMBOcellPolarity25 (https://x.com/HeisenbergCPLab/status/1930179868437721213).

3. The Transparent Star of Developmental Biology

Creaser’s endorsement lit a spark in the developmental biology world. Just four years later, in 1938, L.L. Longley at Brown University published a detailed account of early zebrafish embryonic development. Suddenly, zebrafish were catching more and more scientific eyeballs.

“Wait, aren’t these the little guys that thrive in gross water and don’t mind a chemical bath?” Exactly. And so began a new wave of experiments. Toxicologists jumped on board. Researchers like Hisao Yugao and K.D. Kidmore (a.k.a. the East-and-West duo of developmental toxicology—think Wong Kar-Wai meets Breaking Bad) started using zebrafish to test chemical exposure and pollution resistance. But all of that? It was just the prelude. Because then… the zebrafish met that man. George Streisinger. University of Oregon. If Thomas Hunt Morgan made fruit flies famous, then Streisinger gave zebrafish their Hollywood moment.

Let’s get one thing straight—George Streisinger wasn’t just some curious academic with a fish tank. He was a top-tier geneticist. James Watson—you know, the double-helix guy—once called him one of the most accomplished genetic minds in the United States. Later, he became a member of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences. We’re talking about the kind of legend where, if he casually drops a theory over dinner, you will stand up and take notes.

So when this guy chose zebrafish as his model organism in the 1960s, everything changed. And why did he choose them? Well, hindsight makes it obvious:

- Cheap and easy to raise.

- You can cram hundreds into a small tank with pocket change and a sponge filter.

- Their embryos are transparent, so internal mutations or developmental oddities? Front-row seat.

- And back then, studying genetics often meant dousing your subjects with mutagens and hoping something interesting happened. Luckily for us, zebrafish are basically born with poison resistance turned on—perfect for reckless experimental enthusiasm.

In short, zebrafish were sciency, sturdy, and surprisingly see-through. What more could a researcher want?

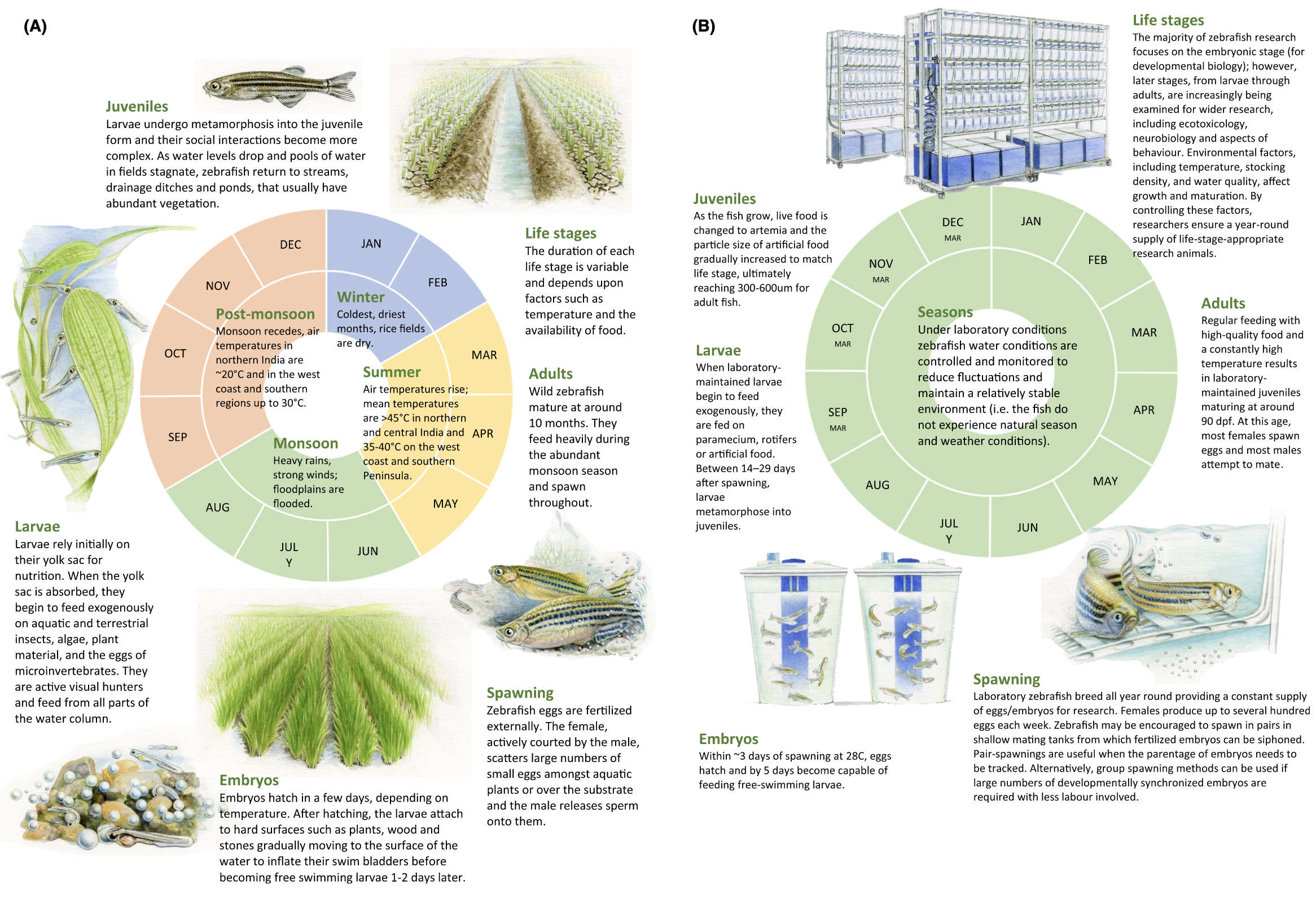

A schematic representing the life cycle and living conditions experienced by (A) wild zebrafish and (B) laboratory maintained zebrafish. Credit: Sandra Doyle. From Lee CJ 2022.

A schematic representing the life cycle and living conditions experienced by (A) wild zebrafish and (B) laboratory maintained zebrafish. Credit: Sandra Doyle. From Lee CJ 2022.

Of course, zebrafish weren’t perfect. Unlike mice, they couldn’t be inbred for dozens of generations to make tidy little “isogenic” lines. Try it for more than a few generations and boom—infertility. Also, their larvae had these annoying pigment spots on the back of their heads, making it harder to observe the brain from above. But Streisinger, as a top-tier geneticist, wasn’t about to let a few fish quirks stop him.

No pigment in the way? He made a golden mutant strain with a spotless hindbrain. Want genetically uniform fish for experiments? He straight-up invented a workaround. He developed a technique where he could double the DNA in a zebrafish egg—without fertilization—creating what’s called a “homozygous diploid.” Then he used that trick, generation after generation, to build what was effectively a lab-grade, asexually derived zebrafish line. Add a little strategic crossbreeding here, a touch of cellular wizardry there, and voilà: You’ve got yourself a lineup of zebrafish with genetic consistency rivaling your favorite mouse strain. This was the turning point. Those golden mutants and Streisinger’s AB strain? Still used in labs across the globe to this day.

But the Streisinger Effect didn’t stop there. His work sent ripples through the world of genetics. Disillusioned fruit fly researchers began defecting en masse, drawn by the siren song of translucent embryos and scalable mutagenesis. One of them was a young scientist named Wolfgang Driever. He’d trained under none other than Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard—a Nobel Prize winner for her work on Drosophila. But after spending a year at Oregon, seeing the sheer potential of zebrafish firsthand, Driever switched teams. He went full fish. Together, his group and Nüsslein-Volhard’s team created over 6,000 zebrafish mutants. They developed the TU strain, now one of the most widely used genetic lines in zebrafish research. Between the mutant collection and foundational strain development, these two teams almost essentially speedran the entire “zebrafish-to-model organism” arc—leaving little terrain for others to claim.

4. Seeing Thought: The Neuroscience Revolution

Now, if all Streisinger had done was turn zebrafish into a solid model for genetics and development, that would’ve been enough. But nope. The story doesn’t stop there. Because once he figured out how to make the zebrafish brain visible—and we’re talking crystal-clear, high-res, no-skull-in-the-way visible—someone on his team had a lightbulb moment. “Well, since we can see the brain this clearly… might as well map the whole thing, right?” So they did. And that brain map? It caught the attention of an entirely new tribe of scientists: the neuroscientists. They were intrigued, and for good reason.

You see, in the wild, small fish like zebrafish are often hunted by predators swooping in from above. But water distorts vision, so direct identification isn’t always possible. Instead, zebrafish evolved a clever defense mechanism: When the shadow above them suddenly starts growing—danger incoming!—they launch into a full-body escape reflex, darting off like an underwater Mario with turbo mode on. This “looming stimulus response” became the perfect playground for brain research.

Want to test how visual input connects to movement initiation? Just project a growing black circle onto the tank. Not enough fancy? Mount a tiny CRT TV on top (yes, this was the ’80s). Cue shadow. Cue escape. Cue science. Since their brains were transparent, scientists could chemically numb or stimulate specific brain regions in real time and watch how the fish’s behavior changed. Some fish didn’t flinch at all. Others panicked at the slightest flicker. Boom—evidence that this reflex is tied to specific neural circuits. It was rudimentary. It was messy. But by the standards of the 1980s, it was straight-up Jedi neuroscience.

If everything so far still sounds relatively normal—fish, tanks, DNA magic—what came next was downright bizarre. Starting in the 1990s, it was as if the entire life sciences community started unlocking new research techniques by asking one simple question: “Would this work on a zebrafish?” And if the answer was yes? Boom. New paper. New citation. New grant. It’s like zebrafish were the main character, and humanity was building its scientific skill tree around them.

In the 1990s, scientists had just cracked something magical—fluorescent proteins. The most famous of them all? GFP: Green Fluorescent Protein. Stick it into a gene, and boom—your cells light up like a glow stick at a rave. This changed everything. Now researchers could label specific cells—say, a handful in a developing embryo—and track their every move as the organism formed, cell by cell. No more guessing where stuff went or how organs formed. Just tag it and watch. There was just one problem. Most animals are opaque. Tag all you want—you still can’t see through fur, skin, or skull. So scientists asked: “Is there a vertebrate animal that’s used in developmental studies… whose embryos are actually transparent?” And the universe answered: Zebrafish. With their see-through embryos and rapid development, zebrafish became the ultimate sci-fi window into embryogenesis. For the first time in history, humanity could record high-definition, full-color videos of life assembling itself from scratch.

Transparent and fluorescent zebrafish.

Transparent and fluorescent zebrafish.

But wait—there’s more. That glowing-protein tech soon leveled up into calcium imaging. Here’s how it works: When a neuron fires a signal, calcium ions flood in. So scientists engineered cells to flash fluorescent light in response to those calcium spikes. The stronger the neural signal, the brighter the glow. Translation: We could now see thoughts as they happened. The brain’s electrical symphony was no longer invisible. Unless, of course, your animal head is not transparent. But not zebrafish. Their brains were fully transparent during early development—almost like evolution saw this tech coming and said, “You’re welcome.” Cue entire zebrafish brains lighting up like a city grid under a time-lapse.

And then came the final boss: optogenetics. In 2005, Karl Deisseroth and his team at Stanford developed a way to control neurons with light. Not just observe—control. Want to turn a neuron on? Shine a specific wavelength. Turn it off? Switch the light. It was neuroscience meets sci-fi mind control. There was only one catch: To get the light into the brain, you needed to implant a fiber optic cable—sci-fi vibes suddenly turned into minor brain surgery. But zebrafish? Didn’t need that. Their see-through brains meant you could beam light in from the outside and still reach deep structures. No drilling. No trauma. No hardware failure because the fish swam into the tank wall. In fact, their watery environment acts like a natural cooling system—perfect for repeated high-energy light pulses. Zebrafish weren’t just compatible with optogenetics. They were born for it.

5. Platform for the Future—On Earth and Beyond

Just when zebrafish were already riding high in the life sciences hall of fame, the 2010s dropped another bombshell on biology: CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing. Suddenly, rewriting DNA wasn’t some sci-fi fantasy—it was drag-and-drop molecular surgery. And guess who became one of the easiest vertebrates to CRISPR? Yep. Our transparent little overachiever. Why? Because zebrafish eggs are fertilized externally. You don’t have to mess with uteruses or perform surgery on tiny embryos. Just microinject those CRISPR components right into the egg. Easy. Fast. Scalable. It’s basically the IKEA of gene editing—some assembly required, but totally DIY. By now, zebrafish weren’t just a model. They were a platform.

And the world took notice. In 1998, the University of Oregon launched the Zebrafish Information Network. By 2000, Europe began sequencing the TU strain. In 2004, the Zebrafish International Resource Center officially opened its doors.

A lot of life sciences university and biotech company got zebrafish swimming somewhere in a plastic tank across the world. Why? Because zebrafish have that one superpower every lab loves: They’re ridiculously easy to keep alive. No fancy mouse cages. No HEPA-filtered cleanrooms. Just some well-aerated tanks, a pinch of shrimp, and a whole lot of scientific ambition.

Ending

In 1976, zebrafish embarked on their inaugural space voyage aboard the Soviet Union’s Soyuz 21 mission to the Salyut 5 space station—the first time these tiny vertebrates were studied in a microgravity environment. About half a century later, on April 25, 2024, four zebrafish boarded China’s Shenzhou 18 spacecraft to begin the country’s first in-orbit aquatic ecosystem experiment aboard the Tiangong Space Station. Living for 43 days inside a completely sealed 1.2-liter tank, they shattered the previous record set by German swordtails, which survived 16 days in space, making zebrafish the longest-surviving fish ever recorded in orbit.

Zebrafish in outer space

Zebrafish in outer space

From their humble beginnings in the sacred currents of the Ganges to their silent drift beneath the starlit expanse of the Milky Way, the journey of the zebrafish is more than a tale of science—it is a quiet meditation on life itself. Suspended in a sealed vessel 400 kilometers above Earth, they glide through orbit as if retracing a cosmic river, where the waters of origin meet the stillness of infinity. In that solitude—between the Ganges, echoing the ancient river they once called home, and the galaxy, reaching toward the stars that now lie ahead—they remind us that life, however small, can rise from obscurity and shine among the stars.

References:

- Episode 39: Biolore: How a tiny fish from India became biology’s most loved animal

- Zebrafish-Wikipedia

- The History of Zebrafish as a Research Model Organism

- Aquarium History Glow in the Dark

- Vintage Aquariums

- Third Paris International Exposition of 1878

- Kimmel CB, Ballard WW, Kimmel SR, Ullmann B, Schilling TF. Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Developmental dynamics. 1995 Jul;203(3):253-310.

- Patterson LB, Parichy DM. Zebrafish pigment pattern formation: insights into the development and evolution of adult form. Annual Review of Genetics. 2019 Dec 3;53(1):505-30.

- Lee CJ, Paull GC, Tyler CR. Improving zebrafish laboratory welfare and scientific research through understanding their natural history. Biological Reviews. 2022 Jun;97(3):1038-56.

- Parichy DM, Postlethwait JH. The biotic and abiotic environment of zebrafish. InBehavioral and neural genetics of zebrafish 2020 Jan 1 (pp. 3-16). Academic Press.

- Eisen JS. History of zebrafish research. InThe zebrafish in biomedical research 2020 Jan 1 (pp. 3-14). Academic Press.

- Pathak NH, Barresi MJ. Zebrafish as a model to understand vertebrate development. InThe Zebrafish in Biomedical Research 2020 Jan 1 (pp. 559-591). Academic Press.

If you found this helpful, feel free to comment, share, and follow for more. Your support encourages us to keep creating quality content.